On January 29, 2025, I finished my novel. I mean, I finished the fourth full draft of my novel and submitted it to my writing group to be workshopped. There’s still work to do but it feels monumental. After years of crashing and burning, taking on too much and self-sabotaging, I finally followed through. I did it. And then I got emotional, and cried on Zoom, and now everyone else in the class knows what a basketcase I am (lol jk they still have no clue.)

Earlier in January, I started a new freelance writing gig and right before that, my agency picked up another client. It was a lot at once, and for a while, the days and nights blurred together. For a while, I did nothing but write and mom (yes, a verb.)

At the same time, my husband started a new job, and the confluence of changes upended our little family’s routine. To cope, our son created his own routine that involved watching his dad drive away every morning, then picking a fight with me over some asinine kid shit, like wanting to wear flimsy rain boots a size too small on a day when it’s 11 degrees and actively snowing. I’d say no, and he’d get mad, and none of us got what we wanted. When I think back on this winter, this year, that’s what I’ll remember: None of us got what we wanted.

On December 29, 2024, our son turned 4 and I wanted to take him someplace that would put candles on a piece of cake and sing “Happy Birthday,” but I didn’t want him to know that the neighborhood restaurants we always go to have cake, so we went to dinner at The Cheesecake Factory. We also threw a party for 22 preschoolers, which was too many preschoolers but also really fun. And toward the end, while all of his friends were still playing, my son lay on the floor in the middle of his own birthday party and said he wanted to go home.

I see so much of myself in him, but I also see that he’s so much better than I have any right to take credit for. He’s quick-witted and determined and empathetic, and his constant growth drags me forward even as every other part of my life feels stuck, waiting, going backwards even—to the parts of my childhood I suppressed; the “feast or famine” anxiety around money. I stumbled upon an article about how women who are exposed to entrepreneurship early in life are more likely to become entrepreneurs themselves. It made me laugh. It made it sound like this was a good thing.

Also in December, my husband and I hosted a last-minute family gathering. It was Christmas Day, and the First Night of Hanukkah, and my stepfather’s birthday—a combined annual celebration he calls Hanubirthmas. He looks forward to hosting; cooking something complicated, something that takes multiple days. But in 2024, my husband and I hosted and my stepfather attended via Zoom from the hospital. He’s been there, for the most part, since before Thanksgiving. He missed the holidays completely. He’s going to miss a lot more, and it’s hard, and I’m really fucking sad.

And I miss my dad from across an ocean (and a few states.) I haven’t seen him in almost a year. When I wake up in the mornings, I sometimes think I can hear the sound of him playing guitar in the other room. When we speak on the phone, he tells me that his condition is worsening; that I might be shocked the next time I see. When I think about how much time I have left with him, realistically, the ground beneath me sharply tilts. He hasn’t played the guitar in years.

The steep, sudden decline of the health of these two men has been destabilizing in a way that, on my worse days, I’m afraid I’m not equipped to handle.

“At the end of the day,” my mom tells me, “the only person you can count on is yourself.”

She wakes up at 5am to cook my stepfather’s meals for the day. He has a severe onion allergy and the hospital staff can’t be trusted to not feed him onions. They keep feeding him fucking onions. They can’t figure out what’s wrong.

There’s just so much wrong—in this world, this country, this body. I feel it in the buzzing circuits of my brain, the aching joints of my fingers, the anxious churning of my gut.

I’ve always been an intuitive person. It’s saved me on multiple occasions, in multiple ways. It’s also gotten me into trouble. I almost always know when something’s wrong, and I almost never know what the something is. As a result, I can wait too long to act. I can be impulsive.

On November 4, 2024, I did something that probably sounds normal to normal people but is absolutely wild in my line of work: I logged out of my personal Instagram account. I’d gotten into an argument with some random dude who became so flustered that he responded to me in Russian. According to the in-app translator, he hoped my next child would be stillborn. I’m not planning to have a next child, but I was watching Bad Monkey and the words sounded like a curse. I knew that, no matter what happened next, I was better off anywhere but the comments on Instagram.

“Who reads the comments on Instagram?” My husband asked when I told him. “I never look at those.”

But it’s my job to look. That’s my defense, but I’m also nosy. I’m fascinated by people. It’s what drew me to acting; what drew me to social media—the allure of VIP access to the human psyche. If I wasn’t the daughter of psychologists, I might have become one myself.

All my therapist friends say that now’s a terrible time to be a therapist, but it’s also a terrible time to be a social media manager. It’s probably, I think, a terrible time to be most people. I hope it’s not a terrible time to be my son.

There’s something wrong with my hands. It’s getting worse. I went to a specialist who told me that she didn’t think it was an early sign of Parkinson’s, but she couldn’t be sure. I couldn’t call my dad to ask, to worry him. When he gets stressed, his symptoms get worse.

I asked the hand specialist if she’d ever watched Better Things. In it, Pamela Adlon wears a brace on her wrist because there’s something wrong with her hands that the doctors can’t figure out.

“You’re just getting old,” they keep telling her. “Your hands are old.”

“Could that be it?” I asked. “Maybe I’m just getting old, but there’s not actually anything wrong?”

“No,” the hand specialist said. “I’ve never seen that.”

I stopped seeing her. I still do the exercises she gave me—”Do your exercises,” my son reminds me when I complain about the pain—but they aren’t helping. Nothing’s helping. It’s getting worse. Late at night, online, I search for a diagnosis. I think it might be related to low blood pressure, or stress, or the cold, or poor circulation. It could be anything, nothing, everything. I’ve been to so many doctors in my life, and every diagnosis I’ve ever received, I’ve had to hunt down myself.

“At the end of the day, the only person you can count on is yourself.”

When she was in her twenties, my mom’s boyfriend ran her over with a boat. It was an accident. She was water skiing. The propellor sliced off her funny bone; scrawled long scars across her chest. Her doctors told her that she’d never use her arm again; that her hand would remain frozen in a claw. She said no.

She bought a tiny motor—the type in a Jacuzzi—and put it in her bathtub. Every day, she sat in the tub and fought the current, stretching little by little until she regained full mobility in her injured arm. She still has her scars, but her hand works fine.

My hands hurt. They really, really hurt. They cramp and tremble. When I type, searing sparks shoot up my wrists. I wear fingerless gloves and take turmeric supplements and do my useless exercises, but I don’t stop writing. I can’t stop writing. I write a whole fucking book.

I want to write here, too, but I don’t know what to say. I don’t know how to get what’s in my head out of my head. There’s so much in my head; it expands, pushes against the backs of my eyes. I’m always crying. I can’t—like so many Americans—figure out what matters, or how to have it.

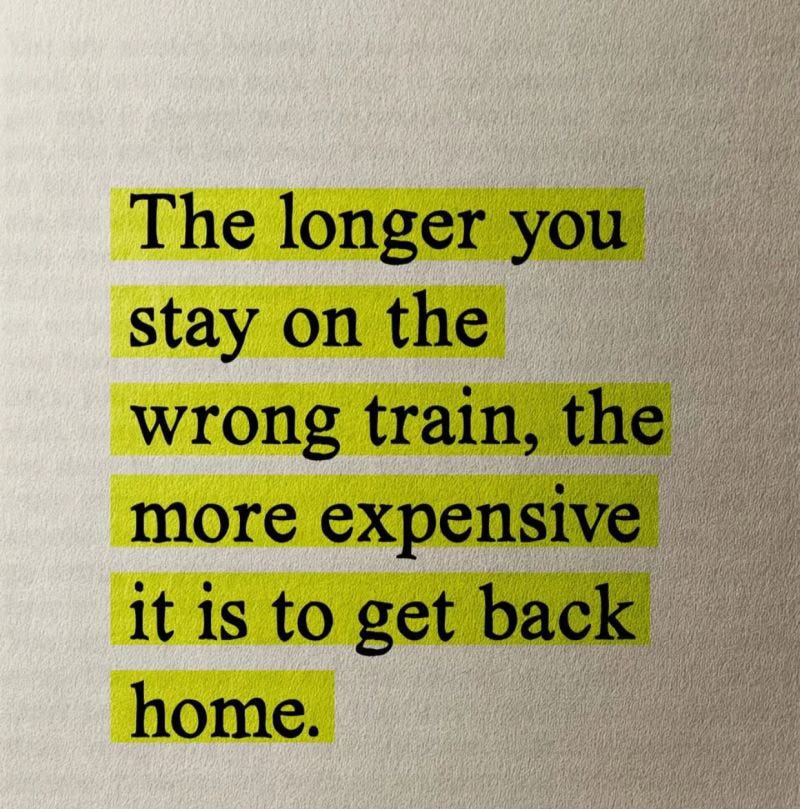

I came across this Japanese proverb that’s been circulating online, passed around by corporate bros on LinkedIn. It’s meant to be motivational, I think, but it made me afraid.

I know something’s wrong, but I don’t know what the something is. I don’t know if the stubborn I’m being is the motor in the bathtub, or the train heading full-speed in the wrong direction. I hope it’s the latter. I hope I don’t crash and burn (again, again, again.) I hope, after a year of so much stress and disappointment and grief, that I can count on myself.

Beautifully raw and honest, my friend.