Every call I received from my grandmother started the same: “Hi, Darling. It’s Grandma.”

“You don’t need to say that,” I’d tell her, laughing. “I always know it’s you.”

She refused to learn that cell phones have Caller ID; that I didn’t know any other women who sounded like her. In her world, everyone sounded like her. Years later, a strong New York Jewish accent still knocks my heart around. Years later, I still have some of her voicemails saved on my phone: “Hi, Darling. It’s Grandma.”

I used to hate the sound of my voice—so high, so young. A friend called it a pornstar’s voice. I could be a phone sex operator, but I wanted to be an actress. My manager made me speak into a tape recorder and play it back, listening for things that were wrong. She sent me to a speech therapist to lower my register. It didn’t match my face. It was holding me back. It was one of many lies I believed.

“Meshugener,” my grandmother would say. “You have a beautiful voice.”

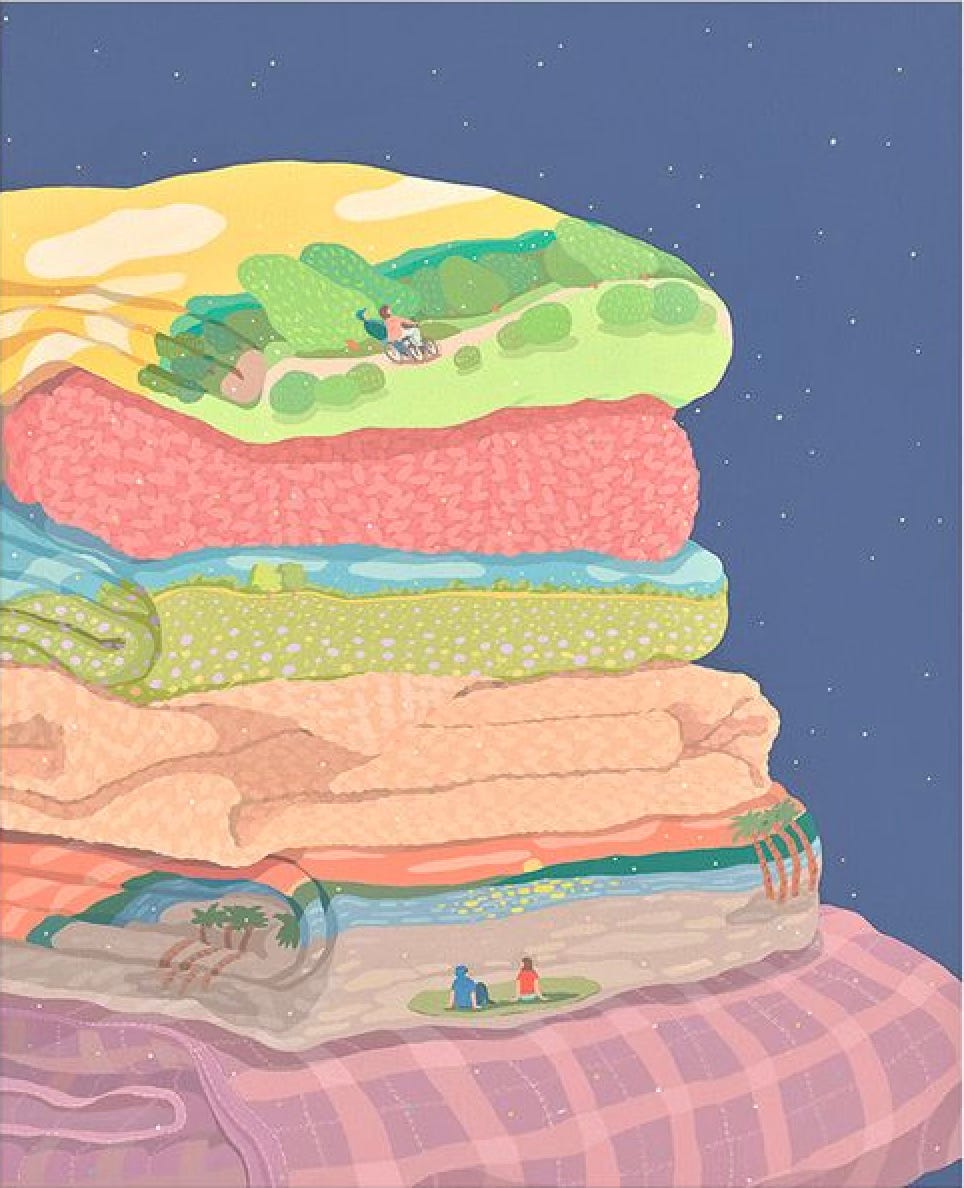

She was a glamorous woman with many health problems that led her through an incongruous knitting phase. She made me a blanket once. It’s red, because when she asked me, I told her that there was a lot of red in my apartment and there was. Since then, I’ve moved many times—to different apartments, then to different cities altogether—but the blanket remains strewn or rumpled or rolled into a ball on the large blue couch in the family room. It’s now my son’s favorite, too. It’s now tattered with use. Several holes are fraying, growing larger. He’s growing larger. He’s at an age where he can break things that can’t be fixed—plants; toys. He keeps ripping the insoles out of his shoes.

“I want that blanket,” he says, pointing toward my lap.

“I’m using it. You have your own.”

“Why?” He asks, pouting. “Why can’t I have that one?”

“I’m using it,” I repeat. “This blanket is special. My grandma made it for me, and now she’s gone and I miss her, so the things she gave me are extra important. It’s like how you love Nini, so when she gives you something, you want to take care of it. That’s what this blanket is for me. Does that make sense?”

“Yeah,” he says. “More muffin, please. With butter and jam.”

Our conversations weave like this, in and out of lucidity. He devours information like butter and jam, distracted but chewing, sticky, dropping crumbs.

“Why do people need sleep?” He asks. “Why do we drink water? Why is it yucky to pick up a dead moth from the ground? Why is it dead?”

My husband and I are coming off a stint of hardcore parenting that included simultaneously potty training and re-sleep training. I would not recommend doing this, but it’s how it worked out and it all went fine—and now our son’s reached a new level of childhood, further from the baby he once was, closer to the person he’ll become. This means that I’ve also found myself someplace new, constantly scouting for the nearest bathroom. I’ve begun to see my age in terms of his: I’m mom-of-a-three-year-old; when he turns four, I’ll turn mom-of-a-four-year-old, and so on. It sounds silly but it feels practical, as his age has far more impact on our daily life than my own. Without him, I maintain friendships across decades, generations. But his age has specific routines and activities; its own logistics and benchmarks and questions.

My son’s curious about words, asking for definitions I scramble to find: except; because; know. He comes home from school and tells me I’m wrong: “You said it was shi shi, Mommy, but it’s called pee. It’s not a pujot; it’s a bellybutton.” I know this is just the beginning. I know that sometimes, I’ll be wrong. I know that no preconception is guaranteed safe passage through motherhood. But on matters of language, I stay strong. In a house with no scripture, we can still worship words.

When I was a child, it was amid a cacophony of accents, dialects, slang: My mother’s Chamorro side, lilting and jolly. My father’s side, booming and sentimental. A series of young European au pairs, each with their own customs and quirks. A revolving door of houseguests; my rhythmic gymnastics coach from Belarus, who called me Lulu and taught me Russian. Their voices echoed around the walls of my childhood home and beyond those walls was Hawaii, with its vast linguistic complexity.

I studied several languages in school—German, Japanese, French. For a time, I was fluent. For a time, I considered working as a translator so I took a linguistics course in college and was unbearably bored. I learned to identify a glottal stop. I learned to drop my almost-island accent; re-say certain things. But small protests remain, sometimes slipping, curling my sentences into sly smiles—and when my son was born, I reverted to words like the comfort food of a fusion cuisine: ”Hamajang is broken,” I tell him. “Manengheng means cold.”

“In which language?” My husband asks. Sometimes I stop to think.

On Sundays, my mom comes to play with her grandson. Once, when she leaves, the block tower they built topples and he says, without hesitation: “Ai adai.”

The phrase fills me like warm soup. I ask him to say it again.

“Ai adai,” he repeats, beaming. “It’s what Nini says.”

He’s a parrot, picking up habits. He can’t pronounce the “ck” sound so he says, “what the fut?” or “my futting phone.” We have no moral recourse. We explain that these are words used only in our home, with our family—and so far, I haven’t received any feedback from his preschool. (Whew.)

His teachers are teaching him Spanish—the alphabet; numbers. He memorizes, but he thinks that “in Spanish” is a catchall for “not how we usually say it.” He makes up gibberish and calls it Spanish: “Abugabugazsa,” he says. “That means door in Spanish.”

“No,” I correct. “Spanish is a real language, like English. It has real words that mean real things. Like Chamorro, what Nini speaks.”

He stares at me blankly.

I ask my husband: “At what age does this become offensive?”

I ask myself, as mothers do, if his confusion is my fault—if my unusual pidgin is teaching him that language barriers don’t exist. I try to be intentional with my words—to use ones that he knows, or that I can explain; to avoid misinterpretation. There’s a Venn diagram somewhere of writing and parenting, and I’m sitting at its center, sounding out syllables, trying to be understood. I comb through my words, pick them apart. I spin inflections, turns of phrase. I weave dialects together and wrap my own weird language around my son, warm and fraying. Years from now, when all that’s left is a tangle of red yarn, he’ll remember my voice.

I enjoyed this real-life account of what it’s really like to move to Bali. Gen Z is right about sleep (and wearing heels; good riddance.) I really loved Babes and also the press Ilana Glazer’s been doing for it (see here and here.) I didn’t know about some of these celebrity book clubs, or this fun fact about asparagus. We need to rewild the internet. You are not a bad frog. Trees might not be able to talk, but they can draw. Why isn’t travel more kid-friendly? A bookish profile on Reese Witherspoon. Creativity in the era of “peak content.” Lol and lol (I’m the first one.)

This was beautiful—and thank you for all the links. I clicked on them all 🙋♀️